[The following article was issued by Bahrain Watch on 11 February 2013.]

With the the start of yet another “National Dialogue” arranged by the Bahraini government yesterday, the Bahrain Watch team thought it would be appropriate to highlight the issue of gerrymandering which will certainly be brought up during the talks.

The question of gerrymandered voting districts has been one of the major sticking points between the government and opposition since 2002, when King Hamad unilaterally imposed a new constitution in Bahrain. The opposition insists that the electoral districts have been unfairly engineered by the government such that the opposition would never be able to win a majority in parliament. (Even if the opposition were to win elections, half of the seats in parliament are appointed directly by the King).

On the other hand, the Government and its supporters maintain that gerrymandering is part and parcel of electoral politics in even the most democratic countries. US House of Representatives member Dan Burton — who took a paid trip to Bahrain last year on behalf of a pro-monarchy group — brushed away criticism of gerrymandering in Bahrain by stating that in the US “and around the world, gerrymandering is a way of life. I don’t know how in the heck you are ever going to stop it.” He went on to give an example of gerrymandering involving himself.

The suggestion that the problem of gerrymandering in Bahrain is similar to that in the United States can only be borne either out of ignorance, or dishonesty. Let’s see why.

In the US, gerrymandering is very much a part of the political tradition, but it is restricted to changing the shape of a district. The 1964 Reynolds v. Sims Supreme Court ruling ruled that the principle of “one person, one vote” had to be applied when defining electoral districts. So although there may be great differences in the demographic makeup of any district, the size of the population in each district must be roughly equal. It is deemed unconstitutional if the difference between any two Congressional districts in a state exceeds one percent.

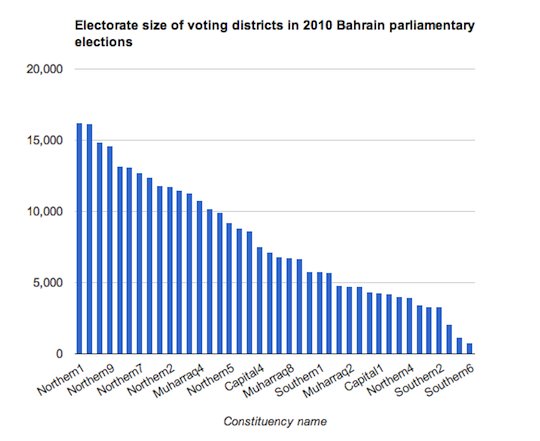

In Bahrain however, the principle of “one person, one vote” was thrown out of the window when the government drew up the electoral districts in 2002. The deviation between the population of the electoral districts here is so big that that it is better expressed in multiples rather than percentages. If we consider the most recent parliamentary elections held in 2010, the largest electoral district (Northern 1) had over 21 times the number of eligible voters than the smallest district (Southern 6).

See the chart below, based on data from the website of Alwasat newspaper for the 2010 elections:

This large difference in voting power alone (“twenty-one persons, one vote”) should be enough to show that the elections are not “fair”. But we can go a step further and see if there is any pattern to which districts have more voting power and which have less. As one would expect when the deviation between districts is so high, the distribution is not random.

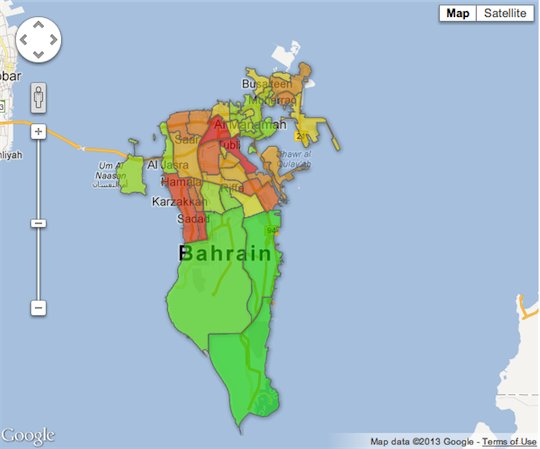

The map below shows the different districts coloured according to the number of eligible voters it had in 2010, with red indicating more voters and green indicating less. Or in other words, more red indicates lower voting power and more green indicates higher voting power for voters in that district.

At first glance, one notices that the districts that have been packed with the most voters happen to cover the mostly Shia villages of the north of the island that are opposition strongholds. The districts with the least voters happen to be mostly Sunni areas in the south that are pro-government strongholds.

The only green coloured district in the Northern Governorate is Northern 4. This district was carved out to connect the Sunni towns of Budaiya and Jasra, and has a total electorate of less than 4,000 voters. Compare that to the directly adjacent Shia districts of Northern 9 and Northern 3, which have over 12,000 and 14,000 voters respectively.

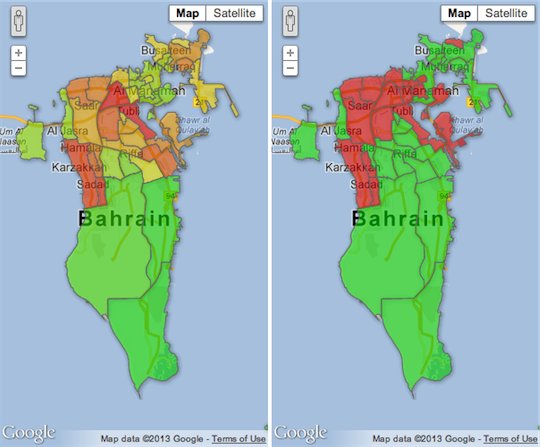

Clearly, this is by design. The pattern becomes more apparent when you put the above map next to one that shows which districts are opposition strongholds. In the map below on the right, the districts coloured red were won by the opposition Al Wefaq party, while those in green were won by pro-government (or “anti-opposition”) candidates.

The five largest districts by electorate were all won by Al Wefaq, while the five smallest districts were all won by pro-government candidates. The average electorate size for districts won by Al Wefaq was over 10,000, while for the rest it was less than 6,300. In total, the number of eligible voters in districts won by Al Wefaq was 181, 238, while the total in those districts won by others was 137,430 — and yet this translated into only 18 parliamentary seats for Al Wefaq, while pro-government groups got 22.

Despite numerous petitions, protests, and boycotts since 2002, for ten years the government refused to even discuss the issue. It was only after the uprising of February 2011 that the government made mention of the subject. After the so-called “National Dialogue” of July 2011, the government “confirmed its intention to establish a committee to re-consider the distribution of electoral constituencies”. However it has yet to publish any details on whether that committee has been formed, let alone the principles that would be used to “reconsider” the constituencies and who would be responsible for carrying it out. Bear in mind that five of the nine members of the committee responsible for implementing the 2011 dialogue belong to the royal family.

Given the outcome of the previous “dialogue” it is easy to be skeptical of the government’s seriousness about resolving this issue in the newly announced dialogue. Maybe the biggest reason for being skeptical is that the man tasked with leading this dialogue, Justice Minister Khaled bin Ali Al Khalifa, has in the past brushed aside questions relating to the blatant gerrymandering problem, by saying that “any member of parliament represents the whole country, he does not represent an area, a sect or a race.”

![[Image from bahrainwatch.org]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/bahrain022113thumbweb.jpg)